THE SMALLPOX VACCINE

- Genaro Pimienta

- May 14, 2025

- 14 min read

Updated: Nov 8, 2025

Humanity was for centuries under the spell of smallpox, a deadly disease caused by a virus named variola. Smallpox was eradicated in 1977, but for this to happen, vaccine technology had to be invented. And it was a worldwide vaccination campaign that drove smallpox to extinction. Nothing else would have eliminated smallpox.

A human-specific Orthopoxvirus, variola was encoded by a DNA genome. To propagate continuously, variola established endemicity in highly populated human gatherings, where it caused an acute, often deadly, disease—smallpox. Adults in endemic hotspots had survived smallpox and were immune to a reinfection. This made smallpox a disease of the newly born and the newcomers, who lacked immunity against variola.

Before its eradication smallpox killed about 500 million people worldwide. To fight back, humans invented an immunoprophylactic remedy that protected against smallpox. Across Asia, Africa, and Europe, humans practiced this remedy in slightly different ways. It was part of their culture; they had Gods for it.

Until one day, in 1798, an English physician named Edward Jenner, gave this ancestral remedy a scientific touch, and named it vaccine. And vaccine it was, which humans used to eradicate variola, and the deadly disease it spread—smallpox.

SMALLPOX IN ANCIENT TIMES

Phylogenetic studies suggest that more than 10 thousand years ago, variola diverged from a common ancestor in West Africa, which infected rodents. Variola became human-specific and lost its animal reservoir sometime after humans discovered agriculture and became sedentary.

Some scholars place the origin of endemic smallpox in ancient Egypt, between the years 1500 and 1100, before the Common Era (BC). Supporting this postulation are three mummies, which feature marks on their skin that could have resulted from smallpox. The problem with this theory is that efforts to obtain molecular evidence of the etiological agent have so far failed. When electron microscopy was used to analyze a sample from the mummy of Pharaoh Ramses V, no smallpox was found; and material from the other two mummies is unavailable.

Scholars also postulate that epidemic smallpox outbreaks emerged during times of prolonged war and social dislocation: the Hittite epidemic (1350 BC); the plague of Athens (430-426 BC); the Antonine Plague (161-180 CE); and the epidemic described by Gregory of Tours in Gaul, present-day Europe (581 CE). But accepting these postulates may be flawed. Because at the time, historical records were unsystematic, and distinguishing between smallpox, measles, and varicella was difficult.

An alternative theory is that endemic smallpox emerged during the beginning of our Common Era. This is the time when historical events associated to smallpox became reliable. The first unambiguous description of smallpox appeared in the year 340 CE, written by Ko Hong, a Chinese physician. Between the 600 and 700s CE, two other scholars characterized smallpox unequivocally: Ahrun of Alexandria in present-day Egypt, and Vagbhata in India.

It was Al-Razi, a Persian physician, who wrote the first clinical description of smallpox in his book titled The Book of Smallpox and Measles (903 CE). Later in 1065, Constantinus Africanus (a scholar at the Schola Medica Saleritana in Salerno, Italy) published a Latin translation of Razi's book. This translation made Razi's description of smallpox available in Europe. It was also the first European document in which the term variola was used in direct reference to smallpox—in Latin, variola means pustule or pock. (While the word variola had been used in 570 CE by Marius, the Bishop of Avenches, he did not directly refer to smallpox.)

Of when smallpox appeared in Europe, we lack historical evidence. Yet, many scholars have long postulated that smallpox emerged in Europe when the Moors invaded the Spanish peninsula in the 700s CE; and that a more pronounced smallpox introduction happened in the 1100s CE, when the crusaders (some of them infected with smallpox), peregrinated back from Minor Asia to their hometowns in Northern Europe.

Smallpox became endemic in most of Europe in the 1400s CE. The survivors became immune to smallpox, but often endured lifelong facial scars, and some lost their sight. The death rate was high: 3 of 10 adults and up to 8 of 10 children died from smallpox. The 1400s were also the days when transoceanic European activity took smallpox to the Americas, where millions perished, and entire civilizations collapsed. It was a domino effect of relentless death.

SMALLPOX INOCULATION

It must have been a collective need to stay alive. But starting the 1500s, different cultures in Africa, Asia, and Europe, discovered (likely each on its own), an ancestral immune prophylaxis procedure, which prevented death from smallpox. Called engrafting, inoculation, or variolation, this procedure entailed exposing a person to the pustulate from a smallpox lesion in a non-lethal manner. The way in which the fluids from a smallpox lesion were processed and administered to a person varied from place to place.

In China, the smallpox pustulate was pulverized and insufflated into the nostrils of a person. In the Bengal region of the Indian subcontinent, the tikadars of the Brahmin sect punctured a person’s upper arm with an iron needle, previously impregnated with smallpox pustulate. In Kenya and Ethiopia, a traditional healer scrapped the wrist of a person with fluid from pustulate matter.

During the 1600s, smallpox inoculation was introduced into the Ottoman Empire, which, at the time, included the Balkans and Greece in Eastern Europe, in addition to a large part of Minor Asia, and the mediterranean littoral in Northern Africa. In Constantinople (present-day Istanbul), smallpox inoculation was practiced by ethnic Greek woman healers who, using a needle, engrafted a small amount fluid from a smallpox lesion to skin cuttings on hands, forehead, and cheeks. For religious purposes these incisions were made in the form of a Christian cross. Along the mediterranean coast of Northern Africa (Libya, Tunis and Algier), pus from a smallpox lesion was rubbed on the scarified skin of a person’s hands.

Variolation was also a traditional remedy in Europe. In Pembrokeshire, Southern Wales, smallpox inoculation had been practiced at least since the 1600s. Known as “buying the pox”, this inoculation procedure was like the one performed in Northern Africa—rubbing smallpox pustulate on the scarified skin of a person’s hands.

Buying the pox was not limited to Southern Wales. It was common throughout Northern Europe in the early 1700s, according to Arnold Carl Kleb, who in his book titled The historic evolution of variolation (1913), wrote the following:

Thus, we hear of a crude variolation in Scotland (Monro I., & Kennedy), in Wales (Perrot

Williams), in Auvergne and Perigord (de la Conadmine), in Jutland (Bartholin), in Duchy of Cleve (Schwencke), and other parts of Germany (The historic evolution of variolation, 1913, p. 71).

Also in this book, Klebs transcribed a poem written in the 1100s, which explicitly mentions variolation as a remedy against smallpox. The poem was written in Latin and reads as follows:

Ne variant teneris variolae funera natis

lllorum venis variolas mitte salubres.

Sen potius morbi contagia tangere vitent

Aegrum aegrique halitus, velamina, lintea, vestes

Ipseque quae tetigit male pura corpora dextra.

(The historic evolution of variolation, 1913, p. 5).

Klebs extracted this poem from Flos Medicinae Scholae Salerni (Salvatore de Renzi, 1879). This was the place where Constantinus Africanus translated Al Razi’s book on smallpox, in which he introduced the word variola.

VARIOLATION

The 1700s in Europe began with a wave of smallpox epidemics in the main urban centers—Berlin, Hannover, London, Milan, Paris, Stockholm, and Vienna. Among the dead, many were members of Royalty. This situation brought much pressure to prominent physicians of the time, who were expected to find a solution against smallpox.

News of the smallpox inoculation traditions practiced China and present-day Turkey arrived in Europe between the years of 1700 and 1716. These were letters addressed to the Royal Society of London, which was in those days the epicenter of modern medicine worldwide. The emissaries were an unnamed trader of East India Company, and three physicians residing in Constantinople: Edward Tarry, Emmanuel Timoni, and Giacomo Pilarino. Despite its compelling nature, the information received failed to impress the physicians at Royal Society. Smallpox inoculation (or variolation) was only be acknowledged by the Royal Society until Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s presentation took place.

(Lady Montagu was married to Edward Wortley, who during 1716-1718, was the British ambassador in the Ottoman empire. It was there when in 1717, Lady Montagu had a woman healer inoculate her 5-year-old son in the presence of Charles Maitland, the embassy’s physician.)

In April 1721, Lady Montagu had her 4-year-old daughter variolated by Dr. Charles Maitland in front of two members of the Royal College of Physicians: James Keith, and Sir Hans Sloane (president of the Royal Society and Kings physician). Also present during the variolation experiment was Lady Montagu's friend, Caroline the Princess of Wales. Princess Caroline was convinced by what she had seen. Yet, before having her own children variolated, she asked for more evidence. This resulted in the variolation of seven inmates from Newgate prison (August 1721), and six orphans from Saint James parish in London (February 1722).

After Lady Montagu’s and Princess Caroline’s demonstrations, several influential physicians abounded in their support of variolation. In 1724, James Jurin (member of the Royal Society) sent a letter to Caleb Cotesworth (Royal College of Physicians) providing statistical evidence that death from variolation was less common than death from smallpox infection. Hans Sloane wrote “On account of Inoculation (1736)” and Richard Mead wrote “De Variolis et Morbilis Liber (1747).” Finally, in 1755, the College of Physicians in London, endorsed the variolation procedure.

COWPOX INOCULATION

If performed incorrectly, variolation could provoke a smallpox outbreak with epidemic potential, or a syphilis co-infection. This was the backstory, when a safer option was brought to the spotlight, which entailed inoculating a person with cowpox instead of smallpox.

In Southern England, cowpox inoculation had been known for decades, perhaps centuries. Milk ladies became immune to smallpox, after touching the pustulate from the lesions, which cows sometimes had on their udders. These lesions were caused by a rare cow infection (cowpox), which appeared spontaneously in dairy farms. That these lesions resulted from cowpox infection was in those days difficult to grasp (microbes and the germ theory were still unheard of), but there was an explanation. Like smallpox, cowpox infects humans. However, unlike smallpox, cowpox, which has a zoonotic reservoir (the cow), is non-lethal to humans.

Knowledge of this traditional remedy transcended the farm dairies. Well-known are the cases of Benjamin Jesty, (Yetminster, Dorset in England), who in 1774, inoculated his wife and two sons with cowpox; and of Peter Plett (Duchy of Schleswig, near present-day Keil in Germany), who in 1791, performed a similar procedure on his family. But Jesty and Plett lacked medical training, and (while safer than smallpox variolation) the cow-to-person inoculation procedure often failed. This is because it was difficult to distinguish a true cowpox from other viral lesions in the udder of a cow, like pseudo-cowpox, or ulcerative mammalities.

EDWARD JENNER’S VACCINE

Like Jesty and Plett, Edward Jenner (an English physician) was aware of the immunity against smallpox, which women who milked cows acquired. Jenner also had knowledge of the dangers that an uncareful variolation procedure could provoke. Because born in 1749, Jenner had been variolated in his childhood and, upon becoming a physician, had started to perform this prophylactic procedure on his patients.

Considered the inventor of the first vaccine, Jenner’s merit was to conceive the vaccination method. He demonstrated that protection against smallpox could be obtained when transferring the smallpox infection person-to-person (arm-to-arm), instead of cow-to-person.

On May 14, 1798, Jenner made an incision on the arm of a 9-year-old-boy named James Phipps (the son of Jenner’s gardener). To the boy’s wound, he added the pustulate from a fresh smallpox lesion, taken from the hand of Sarah Nelms, a milk lady who had contracted smallpox when milking a cow. Weeks later, when exposed by Jenner to smallpox, James Phipps, remained healthy—the vaccination experiment had succeeded. Later in 1798, after repeating the vaccination method on 23 more people, Jenner published a discussion of his findings in An inquiry into the causes and effects of the variolae vaccinae, a disease. In 1801, Jenner abounded on the interpretation of his vaccination experiments, in a publication titled On the origin of vaccine inoculation.

To distinguish it from variolation, Jenner named his invention vaccination, because the remedy against smallpox was vaccinia virus, which lay in the pustulate taken from a cow that had contracted cowpox—in Latin the word vacca means cow. But to Jenner, a virus was a poisonous effluvium (an undefined venom), not a microbe.

These were the 1700s and the miasma theory of contagion was still the accepted explanation for infectious diseases. The epoch’s manner of thinking about infectious diseases is illustrated in Jenner’s book titled “An inquiry into the causes and effects of the variolae vaccinae, a disease.” Let us read the following paragraph from this book:

Morbid matter of various kinds, when absorbed into the system, may produce effects in

some degree familiar; but what renders the Cow-pox so extremely singular, is, that the person who has been thus affected is forever after secure from the infection of the Small-pox; neither exposure to the variolous effluvia, nor the insertion of the matter into the skin, producing this distemper (Jenner, 1798, p. 6).

Jenner also suspected that, like cowpox, horsepox could also be used in his vaccination procedure. Because he lacked knowledge of what a pathogen was, Jenner thought that cowpox and horsepox were the same. But Jenner failed to provide convincing evidence of this horsepox theory. It was John Loyd who in 1801 showed that horsepox inoculation protected from smallpox.

Jenner’s work predated the birth of immunology, microbiology, and virology. Recognizing that germs are the causing factor of transmissible diseases, and that humoral immunity is mediated by antibodies, had to wait nearly a hundred years. For it was until the 1880s when Koch and Pasteur proposed the germ theory and Martinus Willem Beijerinck described the noncellular germs, which years later would be named viruses. Also in the late 1800s, Elie Metchnikoff described innate immunity and Paul Ehrlich laid out the concepts of antibody and antigen.

VACCINIA VIRUS

Jenner’s vaccine was adopted worldwide surprisingly fast. In 1800, Boston and Paris had ongoing vaccination campaigns. So did Berlin and Vienna in 1801.

But whether it was produced from cowpox or horsepox, distributing the vaccine became a problem because the arm-to-arm procedure proposed by Jenner had raised safety concerns. Syphilis co-infections and the use of children for the arm-to-arm transfer, made the procedure dangerous and unethical. A notorious case was The Royal Philanthropic Expedition sponsored by Carlos IV, the King of Spain in 1803. To keep an arm-to-arm distribution of cowpox pustulate, the expedition used 22 orphan boys, while the ship sailed toward Spanish Americas.

Banned in 1898, the arm-to-arm procedure was slowly replaced by vaccination farms. In these farms, calves (and occasionally also sheep or water buffaloes) were inoculated with pustulate matter from either horsepox, cowpox, or a mixture of the two. To reduce vaccine inactivation during transportation, the calf’s lymph was stabilized with glycerol and distributed worldwide from designated centers, like the National Vaccine Establishment in the United Kingdom. Eventually, a freeze-dried formulation of cowpox lymph, coupled to a bifurcated needle, increased the quality of the vaccine used.

Like smallpox inoculation in previous centuries, vaccination efforts in different parts of the world were uncoordinated and performed in different ways. With the passing of time, these uncoordinated vaccination practices engendered an artificial inoculate different from Jenner’s cowpox and horsepox. Its original name (vaccinia virus) was kept, even though the identity and origin of the vaccine used to eradicate smallpox is unknown.

SMALLPOX ERADICATION

Two factors made the eradication of smallpox possible. Variola virus lacked an animal reservoir and was encoded by a DNA genome with a low mutational rate—pathogenic variants, not targeted by the vaccine are nonexistent.

Smallpox was eradicated first in countries with strong health institutions. Great Britain, which eliminated smallpox in 1934, was followed by the Soviet Union in 1936, North and Central America in 1952, and continental Europe in 1953. In Asia, Japan was the first country to eradicate smallpox in 1956, followed in Minor Asia by Turkey in 1957.

As the 1950s reached their end, the number of countries which had eliminated smallpox plateaued. It became clear that eradicating smallpox worldwide required a major international effort. In 1959, the World Health Organization (WHO) intervened and (supported internationally) launched a plan to eradicate smallpox worldwide. But there were logistical complications and lack of funding, which got in the way of the project. In response to this, the WHO started in 1967, an Intensified Eradication Program. This program helped overcome the roadblocks prevailing in many countries, which ranged from difficulties accessing war-thorn countries, like Nigeria during its civil war (1967-1970), to the religious-based resistance in the Indian subcontinent.

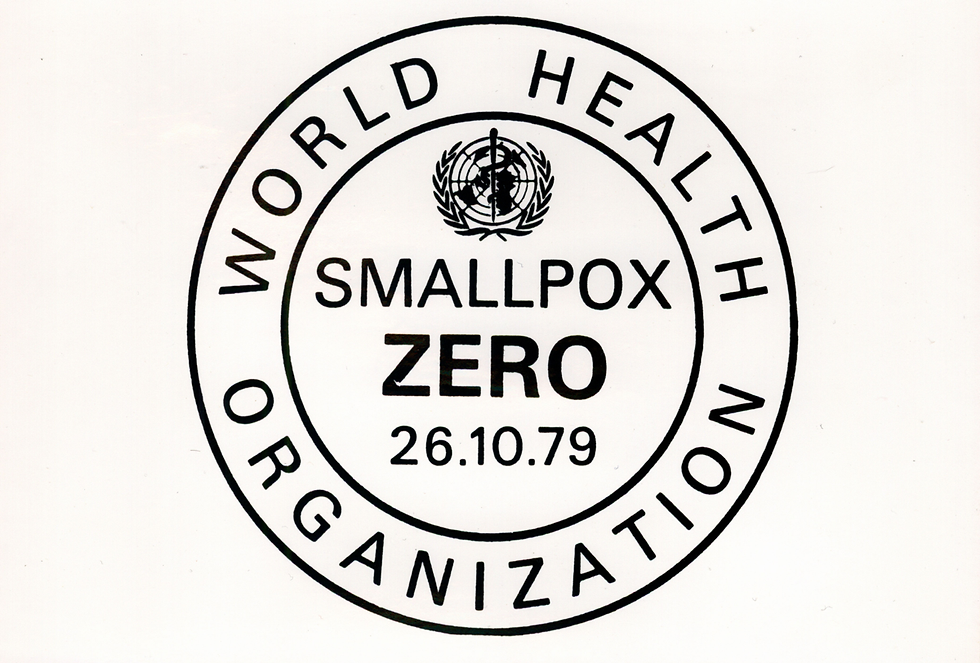

After a final report published in 1979, the WHO declared smallpox eradicated on May 8th, 1980. Rahina Banu, a 3-year-old girl from Bangladesh, was the last person to contract variola major, the severe form of smallpox (30% lethality)—this happened in 1975, and the girl survived. The last case of variola minor (≤ 1% lethality), occurred in 1977, in Somalia.

While controversial, vaccination mandates played an important role in eradicating smallpox. Ring vaccination and epidemiological surveillance eliminated the need to vaccine every person on the planet. In the ring vaccination approach, once a person was found to have smallpox, she was isolated, and her entire family (or community) vaccinated.

VARIOLA VIRUS STOCK

It sounds contradictory but after its eradication, two stocks of variola virus were kept for scientific research. These stocks are stored at the Center for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia, and at the Vector Laboratory near Novosibirsk in Siberia, in Russia. While slated for destruction in June 1999, these smallpox stocks still exist.

The existence of these stocks is problematic because smallpox vaccination programs stopped in 1972. People who were born after 1972 lack immunity against smallpox: an accidental release of the virus from the stocks in the US and Russia will cause a pandemic. This fear is far from being unrealistic. One person died in 1978, when accidentally exposed to smallpox at the University of Birmingham.

In the United States two groups of people are routinely vaccinated: military personnel and laboratory scientists who manipulate pathogenic poxvirus, like monkeypox. And that is not all. Ongoing research has delivered two FDA-approved smallpox inhibitors—brincidofovir and tecovirimat.

RECOMMENDED READING

1.

Emanuel Timonius. An account, or history, of the procuring the smallpox by incision, or inoculation; as it has for some time been practised at Constantinople. (https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstl.1714.0010, 1714).

2.

Pierrot Williams. Part of two letters concerning a method of procuring the small pox, used in South Wales. (https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstl.1722.0046, 1723).

3.

James Jurin. Jurin-1724 A letter to the learned Dr Caleb Cotesworth. (https://www.jameslindlibrary.org/wp-data/uploads/2010/05/Jurin-1724-A-letter-to-the-learned-Dr-Caleb-Cotesworth.pdf, 1724).

4.

Edward Jenner. An inquiry into the causes and effects of the variolæ vaccinæ, a disease discovered in some of the western counties of England, particularly Gloucestershire, and known by the name of the cow pox . (https://wellcomecollection.org/works/krgb7nyy, 1798).

5.

John G Loy. Loy, Dr John G. Account of Some Experiments on the Origin of Cow-Pox. Ann Med. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5110816/ (1801).

6.

Abú Becr Mohammed ibn Zacaríyá ar-Rází (commonly called Rhazes). Translated from the original Arabic by William Alexander Greenhill. A treatise on the small-pox and measles (903 CE). (https://wellcomecollection.org/works/g87eufac, 1848).

7.

Arnold C Klebs. THE HISTORIC EVOLUTION OE VARIOLATION. (https://archive.org/details/historicevolutio00kleb, 1913).

8.

Behbehani, A. M. The smallpox story: life and death of an old disease. Microbiological reviews 47, 455–509 (1983).

9.

Fenner, F. H. D. A. A. I. J. Z. L. I. Danilovich. et al. Smallpox and its eradication. World Health Organization (1988).

10.

Barquet, N. & Domingo, P. Smallpox: the triumph over the most terrible of the ministers of death. Annals of internal medicine 127, 635–42 (1997).

11.

Smith, G. L. & McFadden, G. Smallpox: anything to declare? Nature reviews. Immunology 2, 521–7 (2002).

12.

Riedel, S. Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center) 18, 21–5 (2005).

13.

Li, Y. et al. On the origin of smallpox: correlating variola phylogenics with historical smallpox records. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104, 15787–92 (2007).

14.

Boylston, A. The origins of inoculation. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 105, 309–13 (2012).

15.

McCollum, A. M. et al. Poxvirus viability and signatures in historical relics. Emerging infectious diseases 20, 177–84 (2014).

16.

Thèves, C., Crubézy, E. & Biagini, P. History of Smallpox and Its Spread in Human Populations. Microbiology Spectrum 4, (2016).

17.

Esparza, J., Schrick, L., Damaso, C. R. & Nitsche, A. Equination (inoculation of horsepox): An early alternative to vaccination (inoculation of cowpox) and the potential role of horsepox virus in the origin of the smallpox vaccine. Vaccine 35, 7222–7230 (2017).

18.

Bird, A. James Jurin and the avoidance of bias in collecting and assessing evidence on the effects of variolation. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 112, 119–123 (2019).

Comments